Ti8x Z80 ASM Project Euler 00a

July 27, 2019

Story time & Setting up the development environment

In high school, I was an avid Texas Instruments graphing calculator nerd. I loved that you could program them and I spent way too much time with my face buried in my calculator in physics class (sorry, Mr. Felton), writing various programs and drawing pixelart on the graph screen.

Mona Lisa pixelart I made instead of learning about Golgi bodies

I read the entirety of tibasicdev and knew tons of tricks and hacks to make Ti-BASIC slightly faster (since the language was interpreted, this often involved removing characters and shortening code, also making it less legible in the process on top of the already obfuscating one-letter variables). I even made a series of tutorials with sample problems and solutions in Google Drive and convinced some younger folk to stay after school so I could teach them how to harness the power of their calculator.

I wanted to make a full-fledged game and my friend Ed Ho who was really into rhythm games asked me if it was possible to make one on the calculator. And thus CALCHERO was born (kind of). The idea would have been to make a Guitar Hero clone for the Ti-8X calculator, and the top 5 buttons would be the keys of the guitar, with the Enter button used to strum. As a bonus, it would in theory write music data to the port in real time that could be played on speakers or earphones. Yeah, it was a bold idea but I was determined. I tried at first to use Ti-BASIC but it’s hard to draw even the simplest moving sprites and the music aspect was all but impossible without a more powerful language. I turned my sights on the Zilog Z80, the processor at the center of the Ti-8X Calculators.

Zilog Z80 Microprocessor in all its 8-bit DIP glory

I had seen some crazy things implemented in Z80 assembly, and the Ti-8X calculators have a helpful set of commands that allow for writing, compiling, and running Z80 assembly programs: AsmPrgm, AsmCmp(), and Asm(). I knew that if this Super Smash Bros. “port” was possible, then surely I could get CALCHERO to work.

Super Smash Bros Open made using Axe Parser by Hayleia of Omnimaga

so I read Learn Ti-83 Plus Assembly in 28 Days, and I learned a lot about how assembly works. But I was a bit in over my head at the time, and when the end of the school year came and I went off to college, I got distracted and dropped the project.

Fast-forward 3.5 years and I still love assembly and programming in general, and I’m arguably better at managing time to work on projects. So I sat down and finally reread “28 Days”, and set up a programming environment for Ti-8X Z80 Assembly. This time, I have a much more feasible goal: complete some Project Euler problems using Z80 Assembly. Obviously, I won’t be able to do all of them since some require having a massive amount of storage / clock speed (neither of which is abundant for the Ti-8X calculators), but I think that attempting to solve a handful of these problems will help me hone my assembly programming skills.

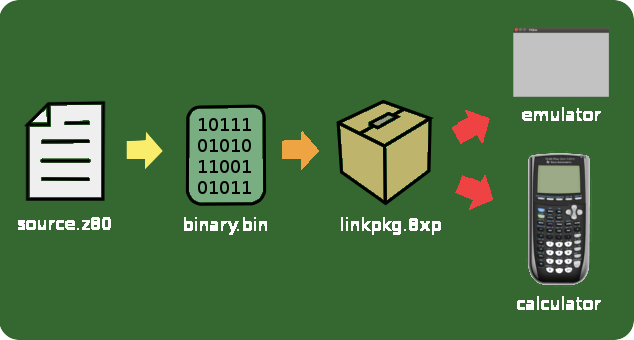

z80 assembly build pipeline

The rest of this post will outline my programming environment on my Ubuntu 16.04 laptop, but I’m sure you could adapt it for other Linux machines easily. You’d probably have to find a different assembler (TASM) and emulator (WabbitEmu) for support on Win/Mac.

First, I will need an assembler to convert the .z80 files (or .asm if you prefer) into binaries that can be run on the microprocessor. I wanted a modern one that was open-source, so if there were any issues I could easily check out the code and figure out what was going on (because not a lot of people do this nowadays so most forums are pretty much dead). I settled on SPASM-ng, an updated fork of the older SPASM assembler that has support for eZ80 now and fixed some bugs according to their README. There wasn’t a lot of documentation on their GitHub about the project, so since it was open source, I figured I’d write my own documentation and in the process learn how the assembler works. I covered all the assembler directives and pre-processor commands, and it was pretty fun reverse-engineering their code to figure out how they all worked without any documentation.

The Ti-8X runs Z80 binaries (.bin) on the actual calculators, but in order to send them to the device, they need to be packed in the correct .8XX file type, corresponding to the model of calculator you’re actually trying to send it to. I found a universal python script called BinPac8x by Kerm Martian from Cemetech that takes any Z80 binary and packages it according to the specified calculator type. According to this file header format specification, I pared down the script so it just created the .8xp files needed for the Ti84+. This also allowed me to more easily learn what the script was doing (I could have just used Martian’s version, but I wanted to understand how it worked so I didn’t accidentally brick my calculator).

Finally, I want to be able to test the programs on an emulator, ideally with some way of debugging the system. That should include the ability to look at registers / RAM and step through code during operation. I tried several options including WabbitEmu but eventually settled on TilEm2, the Ti Linux Emulator. This emulator is pretty nice because it allows you to send .8xp programs to the virtual device right at start-up. It can also accept macros, so after sending the program you can have it automatically start the script inside the emulator. Finally, it has a lightweight yet full-featured debugger, so it fits my needs perfectly.

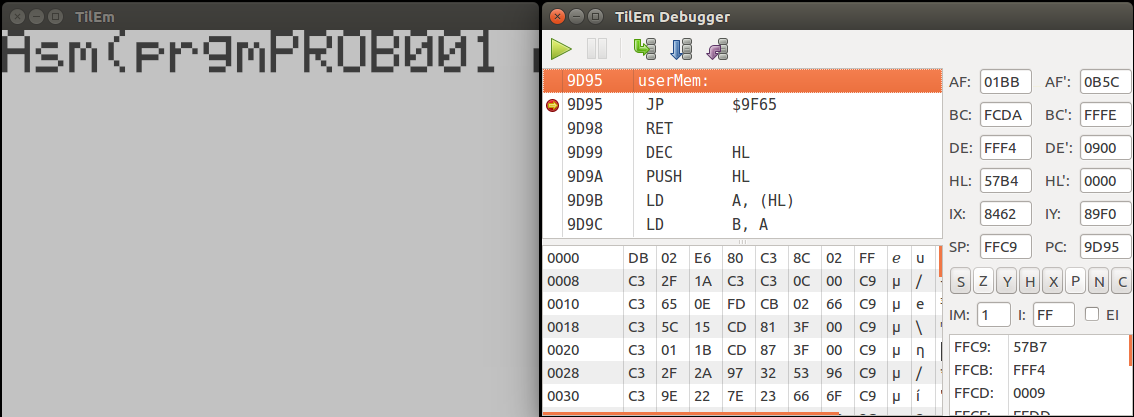

TilEm2 and its debugger breaking at userMem while testing prob001

I wrote a script make.sh that assembles and packages a .z80 file and runs it on the emulator automatically. It takes in a number NNN corresponding to the Project Euler problem I’m working on, and it builds the file named probNNN.z80.

After trying to write and debug some code myself, I noticed that I always want to open the debugger, set a breakpoint at the start of userMem (where user programs start on the Ti8x), and then continue execution until I break on it so I can start stepping through the code. Unfortunately, the macros in TilEm2 only control the calculator, not the rest of the emulator’s features, so I had to improvise. I added a debug switch to make.sh that uses xdotool to simulate all of the keypress events required to navigate the debugger GUI and perform that sequence of steps. Now, when I want to debug the code, I simply add -d to the command line and the debugger will pop up with the program counter already on $9D93 (userMem).

Finally, the build environment was set up and now all I had to do was run a piece of test code. This code doesn’t do anything, but since it builds and runs on TilEm2 without an error message, then the pipeline must be working (if I put invalid code, then the pipeline would error out at some step in the process).

.nolist

#include "ti83plus.inc"

.list

.org $9D, $93

.db t2ByteTok, tAsmCmp

ret

.end

The code above is essentially just a skeleton. It includes a bunch of defines that are relevant to the Ti8x calculators, then indicates that the start of the code is $9D93. Next, it places two bytes into memory that tell the processor that we’re writing an assembly program. Finally, it returns immediately without doing anything interesting but importantly, not causing an error.

Coding skeleton coding skeleton code

That’s all for today. In the next installment, I’ll actually solve the first Project Euler problem! See you then :)